TRADITIONAL ATTIRE

Clans of Ireland commemorates Gaelic traditions, including literature, art, music, government and dress.

There has been considerable interest in early and medieval Irish dress among the membership of Clans of Ireland, but it is generally acknowledged that the public at large are less than familiar and frequently uninformed on traditional Irish dress. This is in contrast to most countries where traditional dress is commemorated and worn on festive and formal occasions.

This Briefing Document is intended to offer, to those who are interested, a short introduction to traditional attire that was widely worn in Gaelic Ireland until sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

Our sources accompany this document.

Early references to clothes in Ireland suggest that in addition to their obvious practical purpose, clothes were, not unusually, an indicator of the status of the wearer.

The basic item of apparel was the léine, which was made of linen and generally dyed a yellowish hue (women usually wore a white leine) by soaking a number of natural colorants including inter alia the boughs, barks and leaves of poplar trees, the bark of wild arbutus, sometimes saffron, salt and urine as a mordant or fixing agent. Natural saffron from the Autumn Crocus was only used after its introduction after the tenth century, by the wealthier, sometimes exclusively and sometimes within the colorant mixture.

The léine was a long ankle length tunic; generally, hitched up to roughly knee length by men. Later in medieval times triúbhas or trews were worn with or without the léine When triúbhas were worn without the léine, it was worn with a short basic shirt or léine ghearr, a type of ionar without the cutaway sleeve design and the regular brat. Women and clergy continued to wear the léine at ankle length. It was gathered at the waist by a crios or belt.

Over this a brat, a heavy wool mantle, was worn tied with a brooch and varying in length depending on social rank, but distinctively longer than similar items of apparel worn in other European countries. This was the most consistently popular item of clothing worn over many centuries in Ireland. The colour was influenced by local availability of dye agents.

The brat was considered to be both garment and house, worn as a cloak during the day and used for sleeping under at night. On the head, a man wore a bairéad or bioraid, dependent on status, a woman wore headgear such as the Lín Caol on the head upon and following marriage, while unmarried women wore their hair plaited and visible. On the feet he or she wore the bróg.

The distinctive Irish clothing was worn by the ‘native Irish’ until the 17th. Century. Its use began to gradually decline from c. 1610, as the influence of the English monarchy, government and laws spread. The attitude of the Tudor government was to dominate politically and socially. The distinctive length of the Irish léine was curtailed and the use of saffron, made from the dried stamen of the autumn crocus, was forbidden in Galway in 1536 and throughout the rest of the country in 1537.

However, woollen weatherproof mantles continued to be worn by everyone: Irish, Anglo-Irish, English; adult, child, male and female; wealthy and otherwise. The poor wore lighter unlined versions, while the most popular form was the fringed mantle with tufted or curled nap. The least expensive form was rough undyed fleece.

By the seventeenth century some who wished to appear anglified on occasion did so by concealing their mantle fringe and wearing a small cape, thus appearing to wear a makeshift version of a French cloak with a cape. Thus, it is concluded that the mantle fringe continued to be a distinguishing feature of the Irish mantle in the seventeenth century. However, by the 1650s it was considered that the Irish were conforming to English dress in general, except for the poor who continued to wear a very basic mantle.

According to Mairead Dunlevy, considered as having been one of the leading contemporary 20th century authorities on traditional Irish dress, “The aim of the government from the mid-14th to the 17th century was to make Irish people abandon their own dress styles — styles which retained ancestral comparisons with those worn throughout Europe — and to follow the styles favoured by the middle and upper classes of England. Under Henry VIII legislation was introduced outlawing the Irish mantle, the use of saffron dye, and the wearing of overly long and full garments.

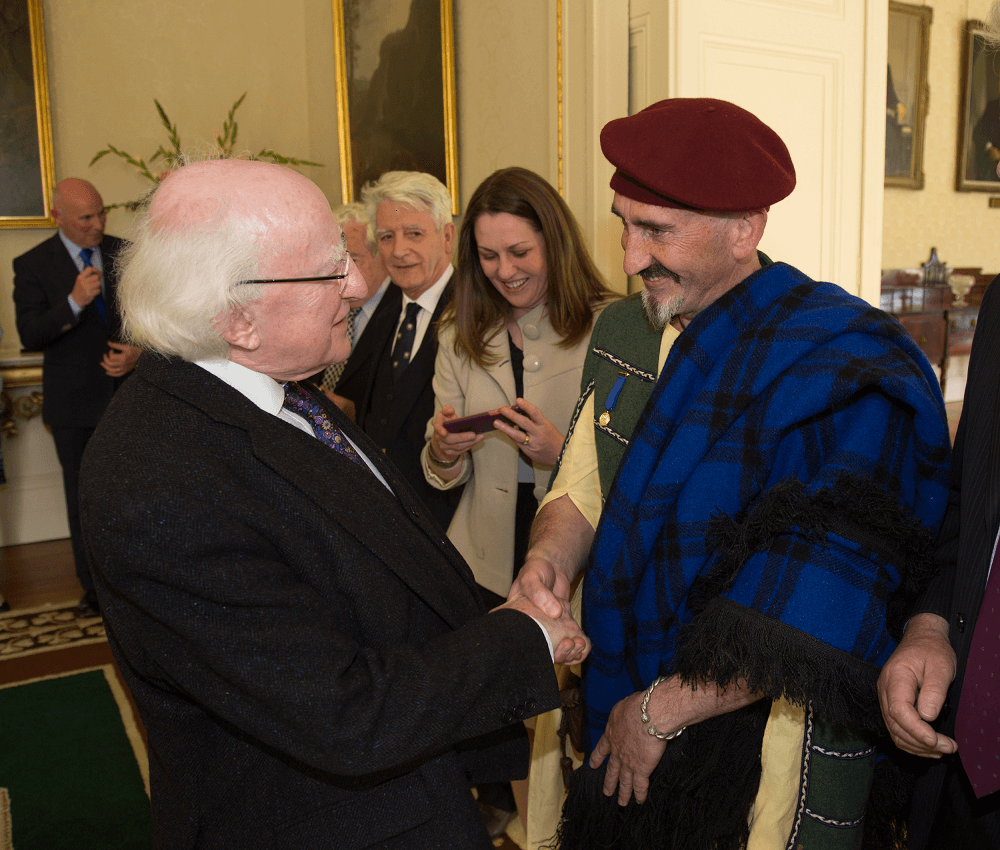

Clans of Ireland is proposing to promote interest in Traditional Irish Dress with the main aim of achieving state recognition for traditional Irish Dress. It is worth considering that traditional dress is the norm for festive and formal occasions in most countries. We see celebrated examples not only with our close Celtic neighbours, Scotland and Brittany, but all-around Europe. In Europe, other than England, (possibly the only European country that does not have an official national costume) it is difficult to recall a region that does not have its own distinctive dress.

Misunderstanding about kilts abounds, The kerns of Gaelic Ireland wore the long léine, frequently dyed in a saffron colour. This is often misinterpreted as a kilt in depictions, so much so that the pipe bands of the Republic of Ireland’s defence forces have adopted it as their modern full-dress uniform. However, we contend that this is a mis-representation of traditional clothing.

Nota Bene. On a recent Saturday, one hundred people were surveyed in Bundoran, Co Donegal and the following is the subsequent report of Prionsias MagFhionnghaile, who conducted the survey: “I asked what traditional Irish dress was. Eighty-seven people had no idea, ten said a saffron kilt, one said tartan trousers, one said Irish dancing clothes…..and one said “a kinda yellow skirty dress thing”. That means only 1% came anywhere near to being correct. A “yellow skirty dress thing” is not accurate but that was the best answer. Ask the same question in any other country and the results would be very different!”

We seek to lobby government departments (particularly Culture and Education), other cultural pillar organisations, interested politicians, the media, universities, museums, RIA, RSAI, world embassies based in Ireland, Irish embassies around the world, and the Irish tourist agencies. Our aim is to create awareness of this lacunae in our national heritage.

Further Notes:

Design of the brat

The following is an extract from the 2010 report ‘Early Medieval Settlements and Dwellings in Ireland AD 400 – 1100’ “However, early medieval textiles and clothes rarely survived except in very extremely waterlogged conditions. The production of textiles and clothes was largely the responsibility of women in early Irish society. They were expected to be expert in spinning, weaving, sewing and embroidery.

“The brat was the most colourful, versatile and warmest garment in the early Irish wardrobe. It was four cornered, roughly rectangular in shape and being of wool was probably treated or ‘fulled’ to a dense finish,” according to Ms. Dunlevy. The process of fulling was undertaken both to make the material thicker and to rid it of oil dirt and other impurities.

Its early design was that of a blanket, but over time the design appears to have evolved to become a shoulder fitted demi-lune shape cloak. Some brats were fringed with a different colour or colours, some of silver and gold thread. Some were shaggy. Some were embroidered.

In the sixteenth century when fur-lined mantles became the norm throughout Europe, woollen weather-proof mantles were worn in Ireland. The fringe of the tufted mantle were thickened at the neck to give a full collar. According to Sir James Ware, ‘Rowes of this shag or fringe were sowed on the upper part of the mantle, partly for ornament and partly to defend the Neck the better from the Cold and along the Edges run a fringe of the same sort of Texture’.

John Lynch wrote in 1662 that ‘Threads flow down from its border in various lengths like the fringes which are usually seen hanging from the curtains of a bed. But on the uppermost border of the mantle several folds of those sledges were arranged which by their swelling proportions were at once more ornamental and concentrated more warmth on the open neck’.

“The brat was the most colourful, versatile and warmest garment in the early Irish wardrobe. It was four cornered, roughly rectangular in shape and being of wool was probably treated or ‘fulled’ to a dense finish,” according to Ms. Dunlevy. The process of fulling was undertaken both to make the material thicker and to rid it of oil dirt and other impurities.

Its early design was that of a blanket, but over time the design appears to have evolved to become a shoulder fitted demi-lune shape cloak. Some brats were fringed with a different colour or colours, some of silver and gold thread. Some were shaggy. Some were embroidered.

In the sixteenth century when fur-lined mantles became the norm throughout Europe, woollen weather-proof mantles evolved in Ireland. The fringe of the tufted mantle were thickened at the neck to give a full collar. According to Sir James Ware, ‘Rowes of this shag or fringe were sowed on the upper part of the mantle, partly for ornament and partly to defend the Neck the better from the Cold and along the Edges run a fringe of the same sort of Texture’.

Illustrations suggest that generally the tufted mantle was worn with the curled side innermost. John Lynch wrote in 1662 that ‘Threads flow down from its border in various lengths like the fringes which are usually seen hanging from the curtains of a bed. But on the uppermost border of the mantle several folds of those sledges were arranged which by their swelling proportions were at once more ornamental and concentrated more warmth on the open neck’.

Fabric of Brat

Wool was always used. Over time the wool became lighter and finer. Twill and herringbone were used regularly..

Colour

It appears that the majority of brat were of a single colour, but colour denote rank so that those of nobility were striped, checked, variegated or speckled with bold colours including; purple or crimson and green, but blue, black and yellow. For every-day wear and for the poor; dun and grey were used.

Colour of Brat

It appears that the majority of brat were of a single colour. For every-day wear and for the poor; dun and grey were used.

Most of the dyes used were of local vegetable origin, berries such as blackberries, flowers such as crocus, bark of trees such as wild arbutus, herbs such as madder (rubiaceae), lichens for brownish red colour and bracken for yellow green. However, other agents, such as shellfish, including dog-whelk was also used. The aforementioned saffron colour, or cróchdae in Irish, derives from the Latin word crocus (cróch in Irish).

Brooches

Originally brooches are thought to have been straight pins made of bone, sometimes with a hole at the head through which a leather lace could be looped. This eventually transformed itself into a bronze pin with a bronze ring mounted and swivelling on the head. A lace could loop from the ring to the tip of the pin to gather the brat securely on the shoulder.

Variations evolved including: the kite brooch, a flap rather than a ring; the penannular brooch, shaped like the letter ’C’, around which the pin could slide and lock in place. These in turn merged to become a pseudo-penannular brooch; most famously exemplified in the Tara Brooch.

Conclusion

Throughout the history of Gaelic Ireland, the Brat was the distinctive item of apparel for men, women and children. Clans of Ireland proposes that the Brat should be seen as a distinctive symbolic item of clothing, as is the case in so many regions of Europe and throughout the world, where authentic culture is celebrated.

It is recognised that the wearing of Gaelic attire diminished through the Seventeenth century and it is hoped that this proposal will generally be embraced for symbolic and festive purposes. Bibliographic

Sources:

Derrick John, The Image of Ireland with a Discoveries of Woodkarne, Ed. John Small, Adam and Charles Black 1883

Binchy, Daniel Anthony, Corpus iuris Hibernica i-vi 1978 (Ed. Binchy)

Fergus Kelly, Early Irish Farming 1997 Early Irish Law Series Vol IV, DIAS (pp 263)

O’Sullivan, McCormick, Barney, Kinsella and Kerr. ‘Early Medieval Settlements and Dwellings in Ireland AD 400 – 1100’ Vol. 1, 2010

Dunleavy, Mairead, ‘Dress in Ireland, a History’;

Lynch, John, Cambrenis Eversus, Volk.II, Ed. & Trsl. Rev Mathew Kelly, The Celtic Society 1850. P. 203

Mac Niocail, Gearóid, ‘Ireland before the Vikings’ 1972 (for ranks within early kinship groups pp 49 – 52)

Ó Floinn, Raghnall, ‘Irish Bogs Bodies’, Archaeology Ireland Vol. 2, No. 3

O’Kelly, M.J. 1958 Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy 57-138

Petrie, George, The Dublin Philosophical Journal and Scientific Review. Vol 1, 1825

Pinkerton, William, ‘The Highland Kilt and Old Irish Dress’, Ulster Journal of Archaeology, Volk. 6, 1858

Ware, Sir James, The Antiquities and History of Ireland (1654 – 8) 1705 p.29

Whitfield, Dr. Niamh, ‘Irish Art Historical Study in Honour of Peter Harrison